A crisis is unfolding across Europe as scores of aging migrants struggle to navigate health-care systems. Official sources estimate that about 7.4% of the EU population—33.2 million people—are non-citizens over the age of 65, and in 2023, almost a third of these older adults reported bad health.

Although migrants comprise a significant portion of Europe’s health-care workforce, they are failed by those same systems. EU governments are creating a care apartheid where those who provide care cannot access it. Migrants constitute a vital segment of Europe’s healthcare workforce. During the COVID-19 pandemic, their contribution was particularly indispensable. According to the WHO, migrants made up 13% of essential workers in the European Union. Across many countries in the WHO European Region, they continue to play a critical role in health and care services. The number of migrant doctors and nurses in OECD countries has surged by 60% over the past decade, underscoring the growing reliance on their expertise.

As Europe faces continued migration and accelerating demographic aging, the treatment of aging migrants serves as a test of resilience. Current policies often change without considering their impact on vulnerable populations, leaving migrants scrambling to understand new requirements and restrictions. For example, Sweden’s Act 2013:407 granted undocumented migrants access to healthcare that cannot be deferred but created confusion about what constitutes non-deferrable care, particularly affecting aging migrants with chronic conditions. Denmark provides only limited healthcare access for undocumented migrants despite international human rights commitments, creating arbitrary barriers.

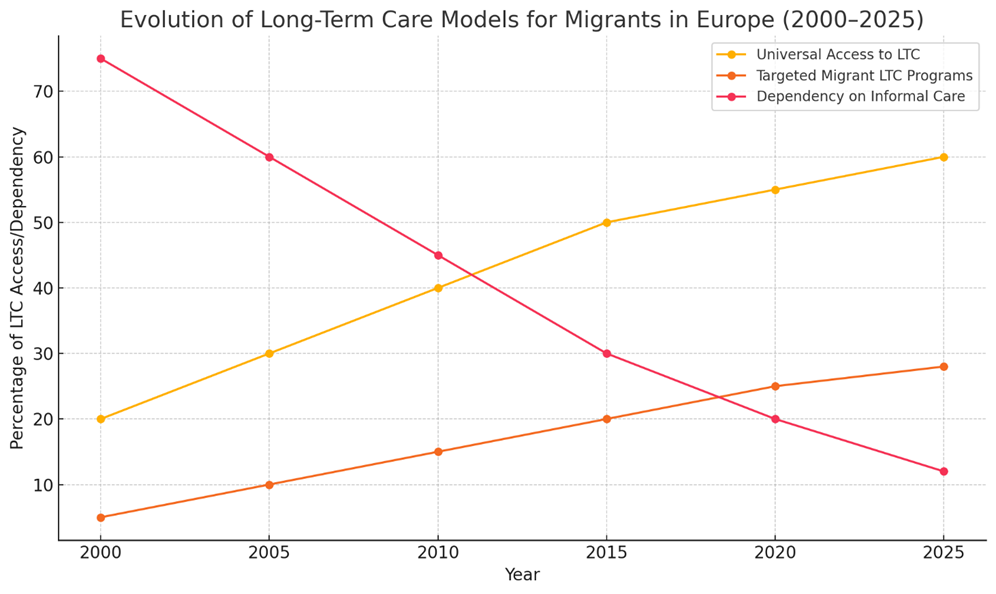

(This conceptual figure synthesizes observed trends in European long-term care systems, including the steady rise of universal LTC access, gradual expansion of migrant-targeted programs, and a marked decline in dependence on informal care. While not based on raw national statistics, the trajectories reflect broad patterns identified in policy reviews by OECD, FRA, and Eurostat).

Studies, such as one on older migrants in the Netherlands, highlight Europe’s growing foreign-born older adult population and project a rapid increase in their demand for long-term care services in the coming decade

A systematic review from Germany found that migrant populations use healthcare services less frequently than native-born residents, not because they need less care, but because they face language barriers, cultural misunderstandings about how healthcare systems work, fear of discrimination, and concerns about their rights to access services. This means health problems often go untreated until they become serious emergencies.

Data from the Netherlands similarly indicates that older Turkish and Moroccan adults are less likely to utilize formal residential care and tend to rely more on home-based care and informal family support compared to native-born populations. This higher reliance on informal family care is often attributed to strong cultural norms regarding family solidarity and caregiving within these communities, as well as potential barriers to accessing formal services.

Concurrently, Swedish statistics show that undocumented migrant communities frequently endure lengthier wait times for healthcare services and often receive care that does not fully address their concerns. Research identifies two main barriers causing these delays: fear of being disclosed and deported by authorities, and structural and psychosocial factors that hinder undocumented migrants from reaching healthcare, given their difficult living and work environments. Additional obstacles include complex bureaucratic paperwork requirements, communication difficulties, financial constraints, and a lack of knowledge about how the healthcare system works. Healthcare staff attitudes toward undocumented migrants also affect their access, as these patients are especially vulnerable due to their legal status and fear of being reported

The irony is undeniable: migrants constitute a large share of Europe’s care workforce, yet as they grow older, these very systems that depend on them fail to meet their needs. It is a troubling paradox, a form of care inequality where caregivers are excluded from the care they once provided to others.

However, Sweden has made efforts to improve access. Before Act 2013:407, undocumented adult migrants had no legal rights to subsidized healthcare and could only access emergency care at full price. Act 2013:407, which came into force in 2013, entitled undocumented migrants to healthcare “that cannot be deferred,” expanding their access to subsidized care. To improve the quality of care, several European cities have piloted culturally tailored interventions that yield improvements in cost-effectiveness and user satisfaction. In that year, Amsterdam began training ethnic community health workers to act as liaisons between the immigrant elderly and local health-care and social welfare services. has demonstrably increased service utilization and self-reported quality of life among Turkish, Moroccan, and Moluccan elders.

In Berlin, partnerships between migrant-focused NGOs such as KuB (Kontakt– und Beratungsstelle für Flüchtlinge und Migrant_innen e.V.), FPZ (supporting healthcare for refugee women and their families) and Medizin Hilft e.V. (providing medical care to individuals with limited access to state healthcare) and care institutions have institutionalized community health workers to act as cultural brokers, enhancing communication, reducing unplanned hospital admissions, and improving caregiver satisfaction among asylum seekers and refugees (although specific quantitative data remain pending)

Across Sweden, linguistically and culturally adapted, person-centered assessment tools, originally developed for older migrants from Finland and the Balkans, have demonstrated improved accuracy in identifying care needs, with follow-up studies reporting better adherence to care plans and reduced emergency interventions.

The economic case is compelling, too. A German study evaluating the CoCare intervention, a coordinated medical care model that optimizes collaboration between nurses and physicians through team-based care, structured treatment pathways, computerized documentation systems, and after-hours medical availability, found that improved care coordination saved each resident 468 euros ($543) in medical costs while reducing hospital stays. When governments prioritize migrant health, everyone wins: patients receive better care, families feel supported, and systems save money.

Europe’s long-term care systems face mounting pressures from demographic change that affect all users, with aging migrant populations presenting additional challenges requiring targeted solutions. While current systems struggle with supply shortages and sustainability concerns that impact native and migrant populations alike, culturally and linguistically diverse communities encounter compounded barriers, including assessment biases, communication difficulties, and limited cultural competence among care providers. This demands comprehensive national strategies, such as those beginning to emerge in countries like Sweden and Germany, which are exploring frameworks for culturally sensitive care.

Addressing these gaps requires evidence-based policy development through more dedicated research on migrant-specific care outcomes, workforce training in cultural competence, and systematic evaluation of existing interventions. Investment in longitudinal studies documenting effective practices across different cultural contexts will provide the foundation for sustainable, inclusive care systems that serve Europe’s increasingly diverse aging population.

Reforming long-term care to serve all of Europe’s aging residents, including those born outside the continent, is a structural necessity for demographic resilience, social cohesion, and health equity.

Europe’s demographic transition is irreversible. The window for proactive policy intervention is rapidly closing. The choice facing European policymakers is clear: maintain systems that exclude growing population segments, or implement inclusive approaches that strengthen care for all residents.

The question isn’t whether Europe can afford to adapt its care systems. It’s whether Europe can afford not to.