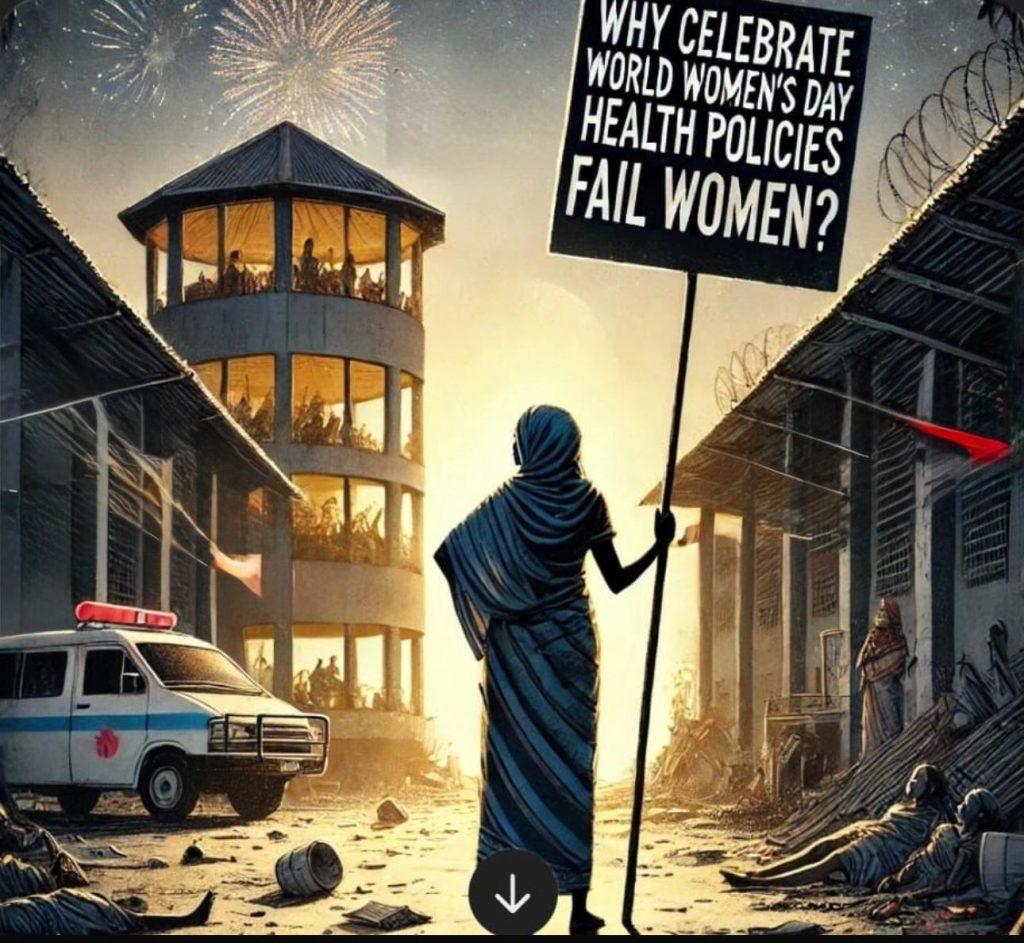

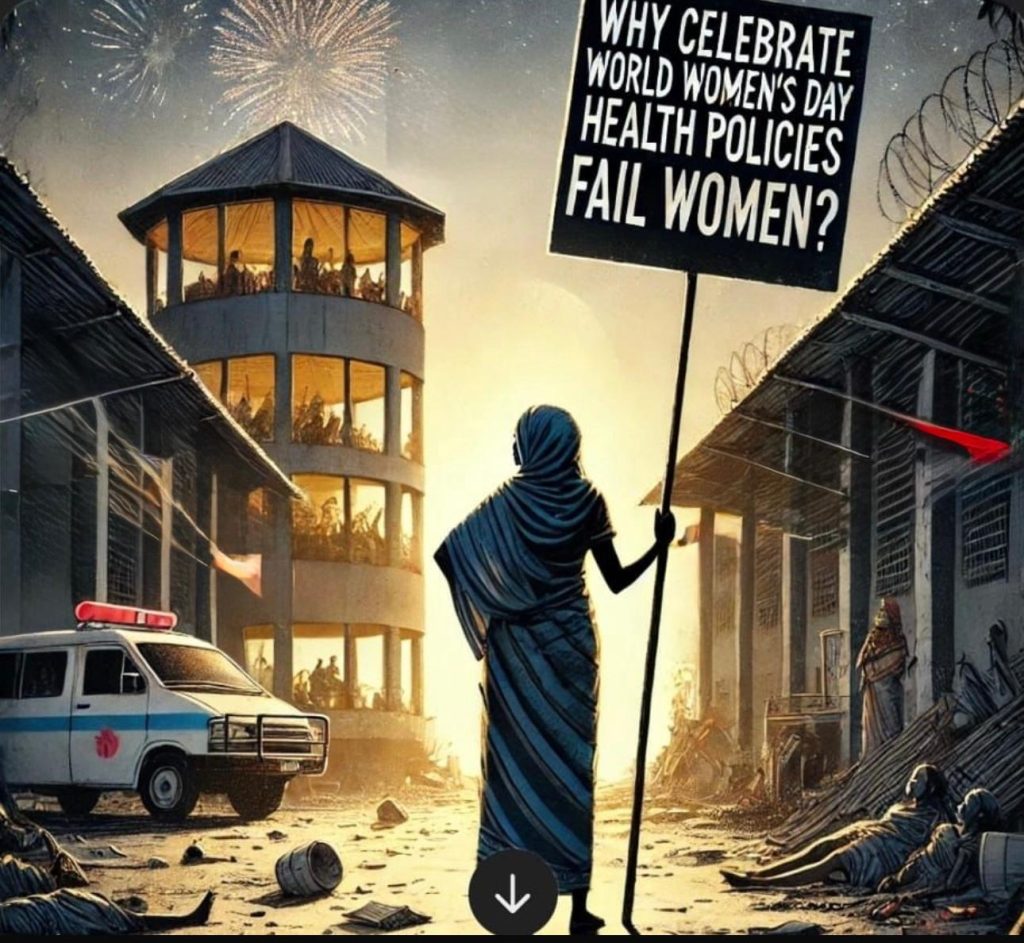

What’s the point in celebrating or fighting for us if our health policies are failing African Women?

Every 8th of March, the world unfurls its predictable pageantry, grandiose speeches, performative panels, and vapid hashtags, all masquerading as a celebration of women.

But what precisely are we celebrating? The unconscionable fact that African women continue to perish from entirely preventable deaths? That gender-based violence festers like an open wound across our communities? The early child marriages where young girls are sold off like cattle to settle debts? The increasing price of sanitary pads, like we choose to bleed? Where basic healthcare is a privilege dangled beyond reach rather than a fundamental right?

We reject this charade of solidarity. Enough with the performative activism; the time has come for radical, uncompromising action. While progress has been made in some areas, significant gaps require urgent attention and policy reform.

This year’s theme, ‘For ALL Women and Girls: Rights. Equality. Empowerment’, must not become yet another hollow promise evaporating into the ether of political convenience. Women globally, particularly African women, do not require symbolic gestures or patronising platitudes; we demand bold, urgent policies that genuinely protect our lives and safeguard our health. The world has betrayed us for generations, and we shall no longer accept meagre crumbs while men in positions of power dictate decisions about our bodies. Health policies must be ruthlessly rewritten, comprehensively restructured, and held rigorously accountable, not tomorrow, not eventually, but NOW.

The stark reality confronting us is brutal and unforgiving: African women are dying preventable deaths every single day because of broken, patriarchal health systems engineered to fail us. How can we reconcile the obscene disparity that condoms are distributed freely and widely in most areas, yet sanitary pads remain an expensive luxury beyond the reach of millions? This cost disparity isn’t merely staggering; it is damning evidence of a society that callously prioritises male pleasure over women’s basic dignity.

Let us be clear: this is not an oversight or unfortunate oversight; it is systematic, institutionalised misogyny embedded within policy-making. Until menstrual products are made as freely available as condoms, any claim to gender equality in health is nothing but a contemptible lie. African women continue to bear a disproportionate burden of preventable health challenges. According to the World Health Organization 2024 report, almost 95% of all maternal deaths occurred in low and lower middle-income countries in 2020.

Although the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) decreased to 34.2% from 2000 to 2020, it remains a disaster in Africa. Over two-thirds (69%) of maternal deaths happen in Africa.

According to WHO African Region Analytical Fact Sheet 2023 reports, the situation remains most dire in South Sudan, where a woman giving birth faces a horrifying 1223 in 100,000 chance of not surviving. Just across the border in Chad, the odds barely improve at 1063 deaths, while Nigeria records a heartbreaking 1047 maternal deaths per 100,000 births.

This crisis is particularly alarming because while some nations have made remarkable progress, others have slid backward into even more dangerous territory. Since 2017, seventeen African countries have seen their maternal mortality rates worsen, creating a patchwork of hope and despair across the continent. Nigeria, once bad enough with 917 deaths per 100,000 births, has deteriorated by 14% to its current rate. Similarly troubling increases have appeared in Guinea-Bissau (9%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (16%), and Benin (32%).

The situation in Zambia has deteriorated dramatically with a 37% increase, while Kenya’s maternal mortality rate has skyrocketed by a shocking 55%. Even Mauritius, despite maintaining one of the region’s lower rates overall, has witnessed a concerning 38% increase. Comoros (21% increase), Namibia (10% increase), and Sao Tome and Principe (12% increase) complete this troubling picture of regression.

Yet amidst this darkness, beacons of hope shine through. Sierra Leone, once among the three deadliest countries for expectant mothers with 1120 deaths per 100,000 births in 2017, has achieved a remarkable turnaround, cutting its rate by nearly 60% to 443 deaths. Tanzania has reduced its rate by 55%, while Eswatini (45%), Mauritania (39%), Ethiopia (33%), and Eritrea (33%) have all made significant strides in protecting mothers.

This contrasting landscape reveals a continent at a crossroads, where a woman’s chance of surviving childbirth depends dramatically on which side of a border she happens to live. Without urgent intervention across all African nations, particularly those where the situation is worsening, thousands more mothers will continue to die from largely preventable causes, leaving behind orphaned children and devastated families.

The inequities extend beyond maternal health. Despite condoms being widely available for free in many African countries, menstrual products remain prohibitively expensive for millions of women and girls. This disparity reflects deep-seated gender bias in health resource allocation, with direct consequences for education and economic participation. When a month’s supply of sanitary pads can cost up to 10% of a family’s monthly income in countries like Kenya and Uganda, menstrual health becomes an economic and educational barrier, not merely a health concern.

We must acknowledge progress where it exists. Rwanda has demonstrated remarkable political commitment to gender equality, with women comprising 61% of its parliament and specific health policies addressing women’s needs, including comprehensive maternal healthcare programmes that have reduced maternal mortality by over 70% since 2000. Ethiopia’s Health Extension Programme has trained thousands of women community health workers, bringing essential services closer to women in rural areas. South Africa’s Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act has reduced maternal deaths from unsafe abortions by providing legal access to reproductive healthcare.

Yet these bright spots remain exceptions rather than the rule. Most African countries still lack universal health coverage that genuinely addresses women’s comprehensive health needs throughout their life cycles. Reproductive health services remain restricted by legal barriers, social stigma, and resource limitations. Mental health support, particularly crucial for survivors of gender-based violence, remains woefully inadequate across the continent.

True progress requires transformative policy approaches that centre women’s health needs. Universal Health Coverage must extend beyond basic emergency care to include comprehensive reproductive health services, preventive care, mental health support, and gender-based violence response. This requires increased domestic health financing, with specific budget allocations for women’s health priorities rather than relying on donor-driven agendas.

The affordability crisis in women’s health requires immediate attention. Following Scotland’s plausible example of making all sanitary pads, tampons and all menstrual products free in 2022, African governments can implement similar policies to ensure no girl misses school due to her period. Kenya has taken important first steps with its menstrual health management policy that provides free sanitary pads to schoolgirls, but implementation remains inconsistent and underfunded. Scaling up such initiatives across the continent would represent a tangible commitment to gender equality.

Maternal mortality reduction requires comprehensive policy approaches including strengthened referral systems, emergency obstetric care facilities, skilled birth attendants, and antenatal care coverage. Rwanda’s success demonstrates what is possible when political will aligns with evidence-based policies. Its community health worker programme, maternal waiting homes near health facilities, and universal health insurance system provide a model other countries can adapt.

This International Women’s Day, we call for concrete policy commitments rather than symbolic gestures. African governments, health institutions, and global stakeholders must prioritise women’s health through increased domestic financing, comprehensive policy reforms, and accountability mechanisms that track implementation. Women’s health is not peripheral, it is central to achieving broader development goals and fundamental human rights.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) cannot continue as the hollow sham it has become. True UHC must encompass comprehensive maternal health, unrestricted reproductive care, robust mental health services, and responsive gender-based violence support systems. Anything less is an insult to the very concept of universal care and a betrayal of African women’s fundamental right to health and dignity. We reject the piecemeal approach that has characterised healthcare provision thus far and demand truly inclusive systems that address the full spectrum of women’s health needs.

The continued restrictions on reproductive autonomy represent one of the most egregious violations of African women’s rights. Women should never have to beg, plead or justify control over their own bodies. We categorically demand free contraception without condescending barriers, safe and legal abortion services free from moralising interference, and comprehensive sexuality education that empowers rather than restricts. The time has come to abolish every archaic law that presumes to police women’s choices and bodily autonomy.

Policymakers have grown comfortably accustomed to delivering flowery speeches and empty promises each International Women’s Day. This time, we demand concrete action, not performative hashtags or recycled rhetoric. If African governments, health institutions, and global stakeholders fail to act now with the urgency this crisis demands, they stand exposed as willing accomplices in the suffering and deaths of countless African women.

The evidence is clear on what works. The successful models exist within Africa itself. What remains is the political will to scale these approaches and the commitment to centre women’s voices in policy design and implementation. Our health is not negotiable. Our rights are not optional. Our wellbeing is essential to Africa’s future.