Health systems worldwide strive for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to provide health services to all without cost by 2035. UHC financing is complicated and requires context-specific solutions. This blog post dives into these aspects because they address key challenges in achieving UHC in Africa, specifically where existing systems might be lacking. Specifically, the post addresses problem-based policy development, the Beveridge and Bismarck models, transparency and accountability from a decolonised, Africentric approach to UHC, particularly in Africa.

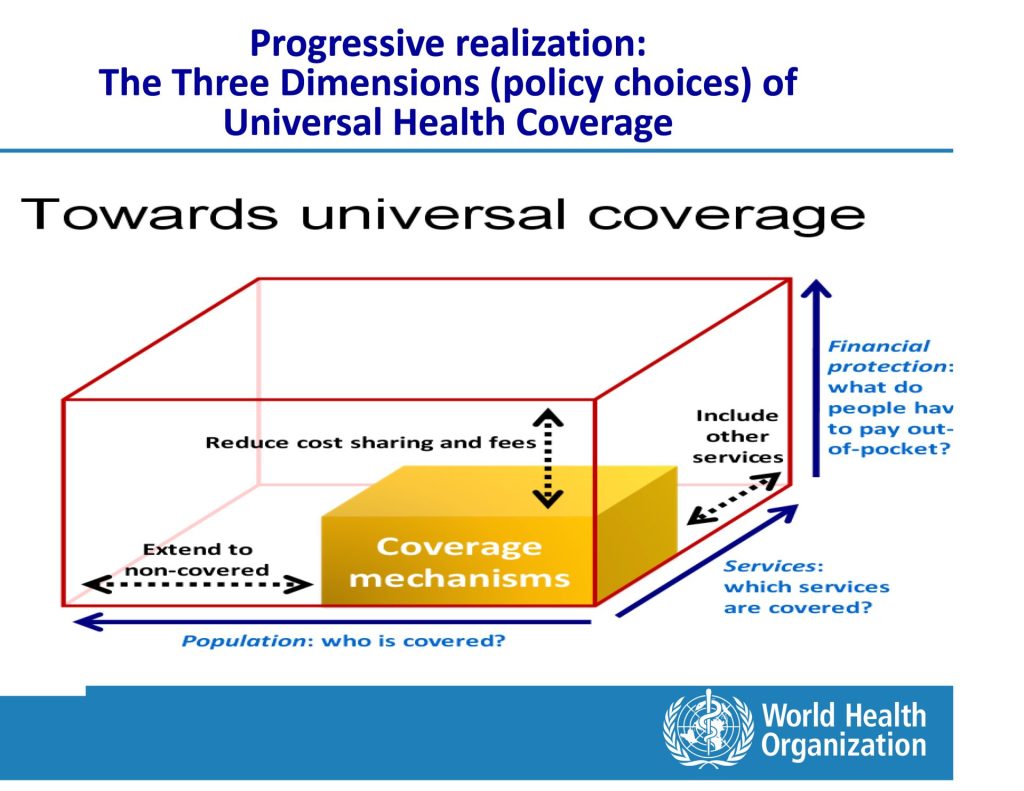

The three core focus areas of UHC, often depicted as a “cube,” (Figure below) are population coverage, service coverage, and financial protection. Population coverage ensures that all individuals, regardless of socioeconomic status or location, have access to health services. It encompasses a wide range of essential services, including prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care. Financial protection aims to prevent healthcare costs from causing financial hardship or pushing people into poverty.

These three dimensions—population coverage, service coverage, and financial protection—work together to create an inclusive, comprehensive, and equitable health system. They address key questions such as ensuring access to necessary health services, preventing financial hardship due to out-of-pocket expenses, and providing high-quality health services that meet the population’s needs.

While population coverage, service coverage, and financial protection are all critical components of universal health coverage, health financing serves as the linchpin that holds these three dimensions together. Adequate and sustainable health financing mechanisms are essential to ensure that all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status or location, have access to a comprehensive range of essential health services without facing financial hardship.

Without proper financing strategies in place, efforts to expand population coverage, increase service availability, and provide financial protection can quickly become unsustainable or ineffective. Therefore, developing robust and equitable health financing systems that prioritise resource mobilisation, pooling, and strategic purchasing is crucial for achieving the overarching goal of universal health coverage and building resilient, people-centred health systems.

Problem-Based Policy Development

Most theories have postulated that the foundation of effective UHC financing lies in problem-based policy development. This approach shifts the focus from selecting which model is needed to addressing the specific problems a health system faces by focusing more on asking what problems need to be solved.

By identifying key issues such as access to care, financial protection, and service quality, policymakers can design tailored solutions that address the unique challenges of their health systems. This approach recognises that each country has its own set of socio-economic, cultural, and political realities that shape the challenges and opportunities for achieving UHC.

Employing Africentrism in problem-based policy development for UHC in African countries ensures health policies are culturally relevant, economically inclusive, and locally managed. Solutions become more accepted because they reflect the reality of the society, and effective by integrating traditional medicine, involving communities in policy-making, and using local languages for health education, solutions become more accepted and effective.

Africentric approaches recognise the socio-economic realities of African nations, such as large informal sectors, and suggest innovative financing mechanisms. This approach addresses unique health challenges, ultimately contributing to sustainable and effective UHC in Africa.

Comparing Health Financing Models

Two prominent models of health financing which have been used as approaches to achieve UHC are the Beveridge model and the Bismarck model.

The Beveridge model of health financing, named after British economist William Beveridge, is characterised by government-provided and tax-funded healthcare services, ensuring universal coverage and equitable access for all residents. In this model, the government owns and operates most health facilities, employs healthcare providers, and funds healthcare through general taxation, eliminating direct charges at the point of service. This centralised control helps contain costs and promote public health initiatives. While the model ensures universal access and cost efficiency, it can face challenges such as funding limitations, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and longer waiting times for certain treatments.

On the other hand, we have the Bismarck model of health financing, named after Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck which relies on mandatory health insurance funded jointly by employers and employees through payroll deductions. This insurance-based system features multiple non-profit insurance funds, known as sickness funds, that cover all employed individuals, with the government ensuring coverage for non-employed groups. The model emphasises regulated competition among insurance funds to maintain quality and efficiency while keeping costs in check. It aims to provide comprehensive coverage and maintain a direct link between contributions and benefits. Challenges include managing administrative complexity and ensuring equitable access for all, regardless of employment status.

However, these traditional models of health financing, like the Beveridge and Bismarck models, have their roots in Western contexts and may not fully address the unique challenges and needs of African countries in particular. Western models often assume a certain level of economic development, infrastructure, and administrative capacity that may not be present in many African nations.

For instance, the Bismarck model’s reliance on formal employment for funding health insurance is less viable in countries with large informal sectors. Similarly, the tax-based financing of the Beveridge model may be challenging in economies with limited tax bases and high levels of poverty.

Moreover, these models do not always account for the cultural, social, and historical contexts of African countries. African health systems often face distinct challenges such as a higher burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases, fragile healthcare infrastructure, and significant rural populations with limited access to services. Additionally, the legacy of colonialism and external dependencies can complicate the implementation of Western health financing models.

Therefore, African countries need more decolonised, realistic and Africentric approaches to UHC that leverage local strengths, integrate traditional practices, and prioritise community-based solutions to create more effective and sustainable health financing systems.

Transparency and Accountability

For UHC to succeed, transparency and accountability are paramount. Citizens need to understand their entitlements as well as their obligations, and there must be clear mechanisms for oversight and enforcement. Most importantly, access to healthcare should not be contingent on employment status, as this perpetuates inequalities and undermines the principles of UHC.

One aspect of accountability that is often overlooked, especially in African countries, is providing comprehensive open data on health system performance, service reach, and most especially health finances. Governments and healthcare providers can promote transparency and accountability by making financial data and reports public. This allows citizens to hold decision-makers accountable for resource efficiency and promotes active participation in policymaking.

Open health finances data can also enable independent analysis, research, and evidence-based decision-making, resulting in more informed and responsive health policies that better meet population needs. Public health finance data can reveal areas that need more investment, inefficiencies, and resource allocation disparities across regions or demographics in Africa, where limited resources and healthcare access are persistent issues. Transparency and public access to health finance information are essential to building trust, optimising resource use, and achieving universal health coverage in Africa.

Achieving UHC requires a comprehensive understanding of how healthcare services are accessed and utilised across different segments of the population. Generalised reports on UHC service coverage may provide an overall picture, but they fail to shed light on potential disparities and inequities that exist within a society. To truly promote accountability and transparency, it is crucial to stratify UHC coverage reports by socioeconomic demographics such as age, gender, economic status, geographic location, family size, and other relevant factors.

By disaggregating data in this manner, policymakers, donors, and stakeholders can gain valuable insights into which specific groups may be facing barriers to accessing healthcare services. For instance, a report might reveal that rural communities or low-income households have significantly lower rates of utilising preventive care services compared to their urban or wealthier counterparts. Such granular data not only highlights areas that require targeted interventions but also empowers communities and advocacy groups to hold authorities accountable for addressing these disparities.

Furthermore, stratified reporting enables more effective monitoring and evaluation of UHC programs, allowing for evidence-based adjustments and resource allocation to ensure that no one is left behind in the pursuit of equitable healthcare access.

In the African context therefore, a decolonised and Africentric approach to UHC financing is imperative. This approach acknowledges the historical legacies of colonialism and the need to develop more country-specific healthcare systems that are grounded in African values, traditions, and socio-cultural contexts. It recognises the importance of community participation, traditional healing practices, and the integration of indigenous knowledge systems into modern healthcare delivery.

Here are some policy recommendations which may be considered;

1. Increase Domestic Health Financing:

Private health insurance and other health insurance systems have indeed played a crucial role in health financing. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that prioritizing state funding is pivotal for achieving UHC and building robust healthcare systems, especially in resource-constrained settings. Governments must prioritise allocating higher budgetary percentages to the health sector, ensuring a steady stream of resources for essential services, infrastructure, and workforce. However, budgetary allocations alone are insufficient; sustainable financing mechanisms that can withstand economic and political changes must be explored.

The implementation of “sin taxation” or “excise taxation” on harmful goods like tobacco and alcohol presents a promising avenue, particularly in African countries. These taxes generate revenue while discouraging consumption of products contributing to health issues, potentially improving citizens’ healthy life years.

By imposing higher taxes on cigarettes and alcoholic beverages, governments can create deterrents while simultaneously raising funds earmarked for the health sector, aligning with preventive healthcare principles and addressing the growing non-communicable disease burden exacerbated by such products.

Sin taxes, such as those levied on tobacco and alcohol, can generate valuable revenue for health financing in African countries. However, a disconnect often exists where these taxes are not fully allocated to the health sector as intended, thereby undermining their potential benefits. To fully capitalise on sin taxation, African governments must therefore implement robust monitoring and accountability measures.

This ensures that the revenue raised is directed transparently and effectively towards strengthening healthcare systems, expanding services, and promoting preventive health initiatives. When implemented properly, sin taxation can not only deter unhealthy behaviours but also provide sustainable financing for UHC efforts. This can improve population health and reduce the over-reliance on impoverishing out-of-pocket payments for medical care.

2. Strengthening Primary Health Care (PHC)

Strengthening primary healthcare (PHC) should be a key policy priority for improving UHC financing in Africa. Investing in PHC infrastructure, workforce, and ensuring well-equipped, accessible facilities in rural and urban areas can lay a strong foundation for delivering cost-effective and equitable healthcare.

A robust PHC system promotes early detection of illness, reduces the burden on higher-level facilities, utilises resources efficiently, manages non-communicable diseases at the community level, facilitates decentralisation, and empowers local ownership. Ultimately, a well-financed and integrated PHC network is crucial for achieving UHC, promoting access to essential services, and fostering a healthier population across the continent.

3. Enhancing Health Information Systems

Effective UHC financing in Africa relies on robust health information systems to ensure efficient resource allocation and accountability. By developing comprehensive and integrated health data collection, analysis, and dissemination systems, policymakers can gain valuable insights into population health needs, service utilisation patterns, and the effects of interventions.

This evidence-based approach allows for data-driven decision-making, enabling the strategic allocation of scarce resources to areas of greatest need and impact. Improved health information systems can also facilitate timely course corrections and optimisations of health financing policies. Accurate data on health outcomes, costs, and expenditure can help design equitable and sustainable financing models, such as risk-pooling and targeted subsidies for vulnerable populations.

Transparent and accessible health data empowers communities and civil society organisations to hold governments accountable for UHC commitments, promoting transparency and citizen engagement in healthcare decision-making. Investments in robust health information systems can enable evidence-based policymaking, efficient resource use, and improved health outcomes in African nations, accelerating progress towards universal health coverage.

4. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) for Enhanced Healthcare

Strategic public-private partnerships (PPPs) have the potential to significantly enhance healthcare delivery and financing for UHC in Africa. By fostering collaboration between governments, the private sector, and non-profit organisations, PPPs can leverage diverse expertise and resources to expand healthcare access and quality. Well-regulated PPPs aligned with national health goals can increase service coverage in underserved areas, reduce the strain on public facilities, and introduce innovative financing models.

Furthermore, integrating traditional health workers into formal healthcare systems via PPPs can be beneficial. This approach preserves indigenous knowledge, supports health education, and improves culturally-sensitive care, particularly in remote areas. PPPs can bridge gaps in service delivery, enhance health-seeking behaviours, and build a more inclusive healthcare system tailored to the diverse needs of African communities.

Conclusion

Financing universal health coverage, particularly in most African countries, requires innovative and context-specific strategies that address the unique challenges faced by each health system. By leveraging problem-based policy development, ensuring transparency and accountability, promoting inter-sectoral collaboration, and adopting a decolonized, Africentric approach, most African countries can make significant strides towards achieving UHC.